Music and Musings #2: "The Long View" and what makes art human

My newest song and some thoughts on AI and art

Hey all,

I want to start this off by apologizing for how long it’s been since my last post. I’ve been aiming for at least one post every two weeks, but my schedule got all topsy-turvy, and this one also took way longer for me to finish up than I planned. Although I haven’t published anything in a while, I have been making some pretty substantive comments over the past few weeks on Notes, averaging ~1,000 words each, which could probably be posts of their own. I’ll have to see about turning my comments into posts moving forward.

If you’re new to this Substack, welcome! This is the second entry in my “Music and Musings” series, in which I share some of my music, artwork I made for it, and, well, muse about it. You can read and listen to the first entry here. Eventually, these songs will go on Spotify and other streaming services, but they’re not available there yet.

I realize that my subscriber base is divided between those who signed up for my philosophical and spiritual posts and those who signed up for my music posts, so I’ve been looking into how to set up different sections for each of those so that everyone can receive only what they’re most interested in. However, even if you’re only interested in one type of post, keep in mind that I do discuss philosophy even in my musical ones, and I may discuss music in my philosophical posts — this one, for example, will be building on the themes I discussed in my previous post about AI art, and the lyrics, which I will also be discussing, are steeped in Buddhist themes. One of my upcoming philosophy/spirituality posts will be about how we can engage with art more deeply — so the two topics are pretty deeply intertwined.

Anyway, that’s all for the housekeeping. Let’s get into the meat of the post.

The Long View

As I recommended last time, take a few minutes to close your eyes and listen. I like to think of this as temporarily renouncing vision.

This song might be my most philosophically interesting to date: it is simultaneously the most human production I have ever made and also the least human production I’ve ever made. Unlike most of my other songs, there is no pitch correction (no autotune), and there is no timing correction (quantization). The tempo also fluctuates, increasing by two beats per minute in the bridge.

Everything you hear is played in or sung by me, entirely unaltered in terms of pitch and rhythm: not a single note of the guitars, bass, bongos, djembe, guiro, tambourine, or vocals was altered in any way for timing or pitch. I did punch-in and comp (edit together) different takes, but none of those takes were altered at all. Occasionally, I looped parts that I liked, but those loops were unaltered, and I only did that a couple times (I think just the guiro and two of the hi-hats in the very opening).

The drums were played in on my electronic drum kit, which recorded MIDI notes that triggered samples from Superior Drummer 3, and the flute was recorded with MIDI as well, but this time played in on a keyboard and triggering a flute patch from East West RA.

Here’s how the process went. At first, I wanted to do this entirely without a metronome to retain all of my natural timing, so I sat down at my drum kit, imagined the song in my head, and played along to it. Then, I recorded all the other parts in a single take from start to finish to get the most live feel that I could. To be clear, I didn’t only record one take — I just made sure that each take I did was from start to finish, so that each take was like one unified recording of the band playing together. I think I ended up doing maybe a few punch-ins, but they were minimal.

This…did not work that well. Turns out that it’s extremely hard to do that, and the timing was a bit all over the place. It wasn’t terrible — was still listenable and there were some parts that I thought really vibed, but it was not as tight as I wanted it to be.

So, I decided to compromise: I wouldn’t use any pitch or timing correction, but I’d allow myself a metronome and as many punch-ins as I needed. However, I did like some of the tempo variations of that initial live version, so I had the metronome speed up and slow down for the bridge.

If you’re not a musician or producer, you’re probably not entirely sure what I mean by timing correction or quantization. The best way to explain it is visually.

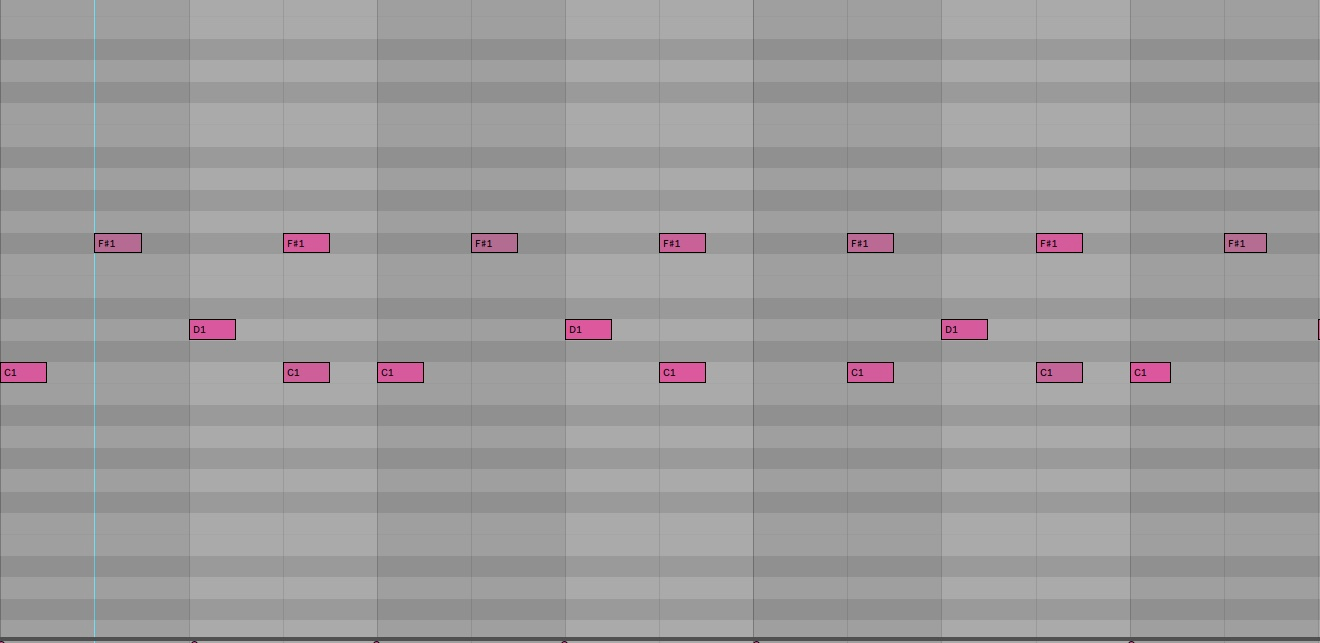

Here’s what a chunk of the final tambourine take looks like, for example:

Those vertical lines represent where a perfectly timed eighth note would fall. If this were played by a drum machine, you’d see that each part of the sound wave would fall exactly on the line. But as you can see, my tambourine hits were slightly behind the beat (generally around 5-30 milliseconds). Although it’s not perfectly in time, these micro-timing differences help give music a human feel, and they can really add to the groove. They are noticeably absent from a lot of chart toppers, although some artists are attempting to add them back in.

You can see what rhythmic quantization does most clearly with the drums. Here is what a piece of the drum take looks like (the drums were recorded via MIDI, which is what you’re seeing below):

Notice again how those notes are not all perfectly aligned to the grid. Most hits are a little early (if you’re curious, F#1 is the hi-hat, D1 the snare, and C1 the kick). In many productions, these hits would be quantized or “snapped” to the grid. That would turn the above take into this:

As you can see, these notes are now perfectly aligned with the grid. But when it comes to music, perfection is often boring, and it can detract from the groove, which thrives on human imperfections. The fact that the drums are slightly ahead of the beat and the tambourine slightly behind gives the beat something of a laid back feel. Stewart Copeland of The Police is known for playing slightly ahead of the beat, for example, which gives their music a more driving or aggressive feeling, whereas John Bonham played a bit behind the beat, which helped give Led Zeppelin their heavy feel.

Overall, this is about as human and as natural as you can get. Comparatively, it is far more natural than the vast majority of modern music: pitch correction and timing correction are standard in music pretty much across the board (excluding jazz, classical, and some indie music), and almost anything you listen to will use them to some extent.

So, why did I put myself through this when no one would expect me to?

Because I wanted to change the timbre of my voice with AI, and I wanted to balance that out.

Gasp! Eek! “But AI is so inhuman, so soulless”, you might say (less likely to say the latter if you’re here for my Buddhist content, I’d imagine). But that’s the interesting part. Your reaction to this reveals what it means for something to be human to you: is humanity based on action? Or is it pure biology? A combination of both?

Let me explain. First off, let me be clear that I was using a voice changer (Sonarworks SoundID VoiceAI) that only allows you to use the voices of singers who have specifically consented to have their voices included in this tool. As far as I understand it, when you purchase the the plugin, they get a royalty payment. The plugin runs locally, so the energy usage is limited to my laptop’s limits — if using this AI is an ecological concern, so is making music on my laptop in general. Based on that, ethical concerns should be minimal.

But what about the humanity of the vocal performance? Doesn’t using an AI destroy the authenticity? Well, it depends on what you care about. The AI retained every aspect of my performance except the timbre: my pronunciation, dynamics, intonation, pitch, vibrato, and timing were all faithfully retained even with the AI voice changer enabled. Even my mouth shapes and the tones they created were basically retained by the AI, and you can hear that when it moves from a dark to a bright tone. In other words, my vocal style and unique vocal fingerprint remains. The only thing that was altered by the AI was the timbre of my voice — the one thing that I can’t change no matter much I practice or how hard I try. My vocal cords are my vocal cords. That won’t change, save for an accident or a medical procedure.

That brings me back to the original point: how you react to knowing that I used an AI voice changer says something about your values and what it means for something to be human. If you think that the performance remains human despite using a voice changer, then you likely view humanity as based on action: the actions recorded in the performance were entirely human, and that’s what matters. Yes, you may hear a few glitches at points, but if a human plays a synth and the synth glitches, we would still consider that a human performance. You would simply consider this “playing” an AI. In other words, our humanity is based on our ability to make choices and the unique way in which we interact with the world, which includes tools and technologies.

On the other hand, if you think that the AI voice changer destroys the humanity of the performance, then you likely view humanity as purely biological or material: despite the fact that the recording retains my vocal fingerprint and all the nuanced choices that went into my performance, it all boils down the material of the instrument, and that material is not human. Humanity is fundamentally based on the soft, wet tissues that make up our bodies.

I don’t blame you if you take the latter stance. I struggle with it myself — something feels deeply wrong about this. But denying the authenticity of this performance seems equally wrong. If our humanity is based purely in biological material, what does that say about people with prosthetics, or people like Stephen Hawking, who need to speak through a computer? What does it say about the possibility of mind uploads? And even more simply, does this stance entail that playing instruments is inherently inhuman, as the sound is not produced by human tissue? Or does the interaction between one’s fingers and the instrument count as human? If so, does that imply there is a specific chain of physical contact that must be maintained for something to be human, i.e. human tissues must touch guitar strings, and those vibrations must be recorded? Or can human tissues simply make contact with a MIDI keyboard or a mouse? What’s the threshold?

In my opinion, it seems that there really is no clear argument here outside of the gut response, and any arguments we provide are just justifications for our initial reactions. That’s not necessarily bad — the idea that morality is always led by emotion is fairly popular. But it should give us pause.

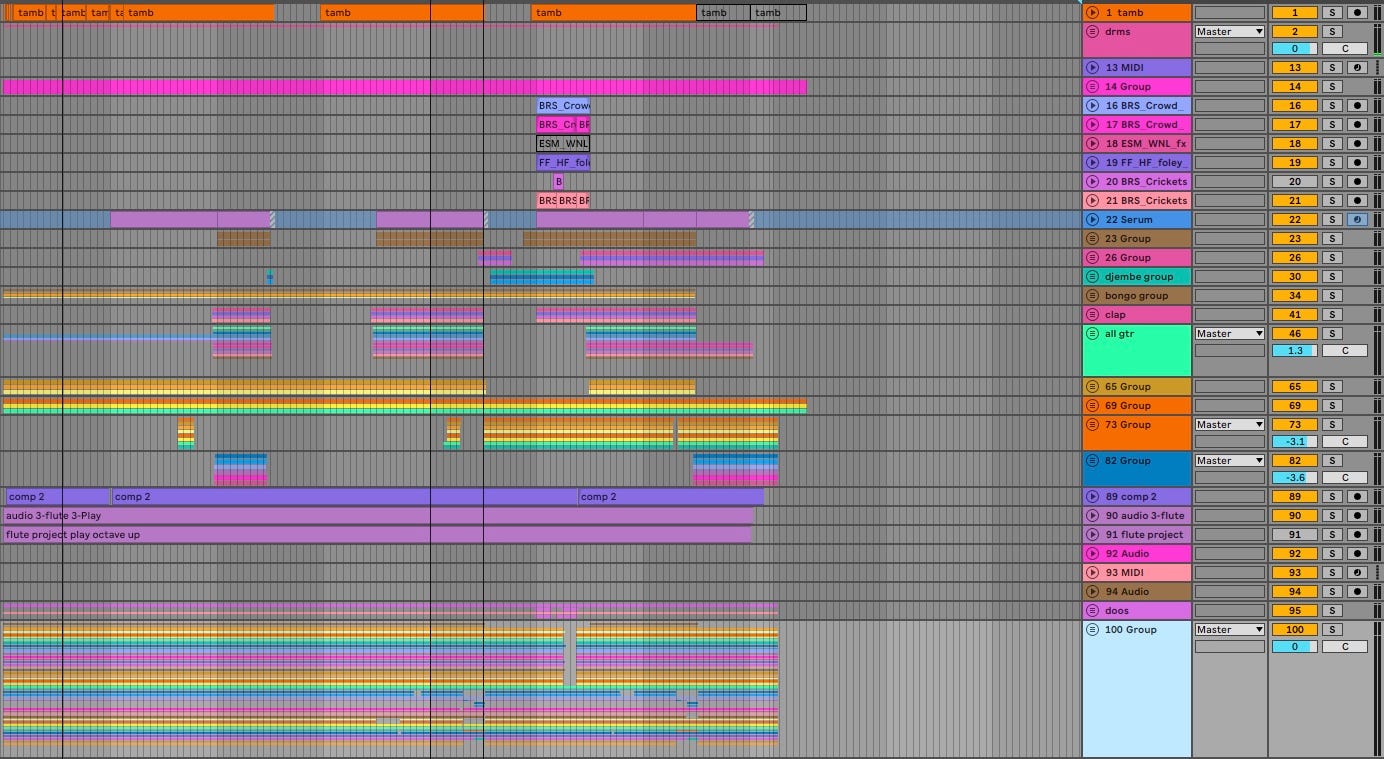

Many of you who believe the AI removes humanity from the performance will probably try to justify that gut response by saying that it’s cheating or lazy. Let me try to stave that off a bit by showing you an example of what goes into a production like this (if you’re a musician yourself, you can likely skip over this part, there’s nothing unusual here). This production includes 149 tracks in the full mix. Here’s what that looks like:

You’ll notice that the track count on the right ends at 100. That’s because that’s the vocal harmony group, and there are 49 tracks within that folder. Any time you see a track that says “Group”, that means there are more tracks hidden within it. You can see the visual representation of those hidden tracks in the thin, faded bars on the left.

But this is just the full mix. I had other project files for the vocals, bass, and drums. Here is what the vocal project looks like, for example:

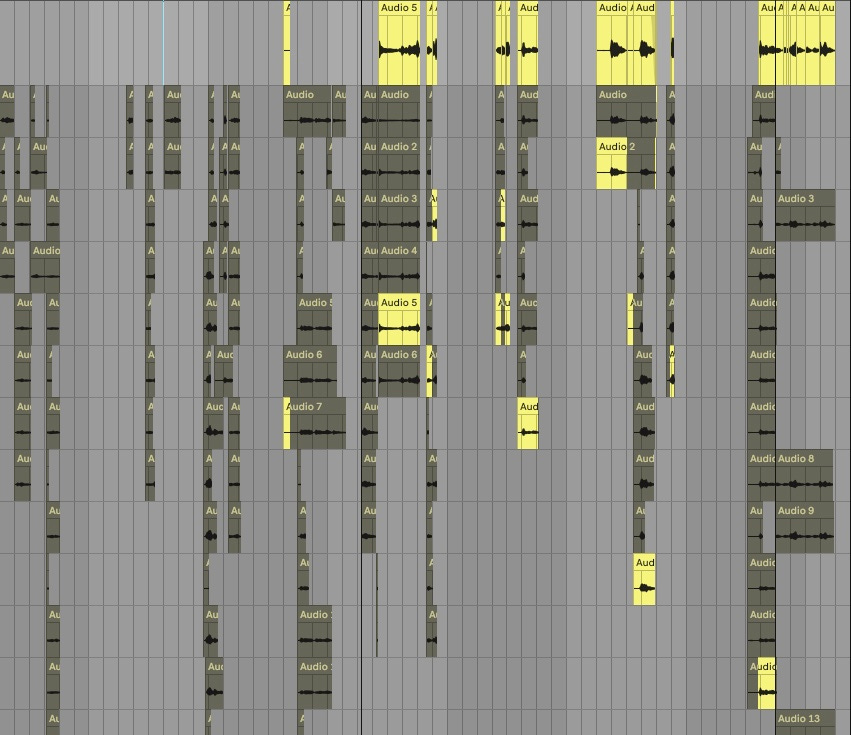

And even this isn’t showing the full picture. Let’s zoom into one of those yellow bars and see what goes into a single track:

Pretty much every line you see see on those projects above expands into something like this — some lines have fewer takes, and some lines actually have way more. What you see here doesn’t even show all the takes for this one track, which was just for one section of the song — they couldn’t fit on the screen.

And that’s just the raw takes. Then those takes need to be mixed. Here’s what the processing on just the drums looks like (again, couldn’t fit it all on the screen):

Each track needs to be processed manually like this to make them gel together sonically (some plugins, like soothe2, which tamps down resonant frequencies, use basic forms of AI, but most don’t, and soothe2 has been a mainstay in the industry since at least 2016). Once the whole mix is done, I export it and bring it into a separate mastering project. Here’s what the processing on the master looks like, again trying to fit as much as I can on the screen:

All this is very standard. I’m just attempting to show that even with the AI voice changer, there is a huge amount of work that still goes into this, and the vocals required a huge amount of work too — there’s no way to visually represent the decades of vocal and ear training practice that made it possible for me to hit these notes, which are quite high in my range.

As Ted Chiang puts it, there are still a lot of choices that need to be made even with the voice changer.

In fact, using the AI voice changer actually made more work for me: instead of just recording a good vocal take and leaving it, I had to choose a voice that fit the song and then record each vocal take into the voice changer using the “Capture” button in the image below and let it process. Sometimes, it didn’t process well, which meant I had to redo takes until I found one that the AI played nicely with. For dozens of vocal tracks, that’s quite a bit of work — much more than if I hadn’t used the voice changer.

As you can see, this is not done out of laziness — one does not usually do more work in an attempt to be lazy. It’s simply an artistic choice. I’m Otto the Renunciant. Renouncing my voice and my body is part of the package.

So if it’s not unethical, and it’s not lazy, what exactly is it that bugs us about something like this? Is it what it symbolizes, and what it means for us as a society?

Well, the lyrics are about precisely that.

The lyrics

I thought this was a perfect song to try the AI voice changer on because it fits with the theme. Here are the lyrics:

I don't wanna wake up honey, I just need a break from the misery. Seems everything's illogical, and there's nowhere left to go, the front line for the truth is on a talk show. And prudence is a fable lost on my modern mind, endeavoring to see behind it all, behind the wall. Too high up to touch down, point that finger at the moon. Ancient forces in my mind, that distant feeling like I'm not alive. Paint the picture of my life, wax wings and I flew too high. Ancient forces in my mind, that distant feeling like I'm not alive. The long view, the long view. I just gotta take it in the long view. The long view, the long view, I just gotta take it in the long view. Take care, brother. Don't stray too far. Sages have walked in front of you, pointing out the things to do. But on a Friday night you're an animal, And you say that you just need to feel all right. Well, you can say what you want to, that doesn't make it all all right. We're too high up to touch down, point that finger at the moon. Ancient forces in my mind, that distant feeling like I'm not alive. Paint the picture of my life, wax wings and I flew too high. Ancient forces in my mind, that distant feeling like I'm not alive. The long view, the long view. I just gotta take it in the long view.

I won’t go too in-depth on the meaning here as I know this post is already getting long, and there’s some merit to leaving some things up to interpretation. But I’ll give a general overview of my intention, and you can decide for yourself whether the intention matches the lyrics.

The song is called “The Long View”, and it’s about how our modern era fits into the longer span of human history. Although we tend to think of ourselves as highly logical and scientific beings who have moved beyond myth and legend, there is a creeping sense that we have lost our grounding. The institutions we relied on are in chaos, and our attention spans have shrunk so much that instead of looking for truth from deep study or first-hand experience, we just look for sound bites from podcasts, which are essentially talk shows.

Now, I don’t actually have anything against podcasts, but what I do take issue with is that podcasts are designed to be something we put on in the background. There is a huge difference between sitting down and listening to a podcast and simply hearing it in the background as we go grocery shopping or clean the dishes. We now see truth as a commodity, and we have lost all respect for it. We hardly ever see anything as deserving of our full, undivided attention — Netflix is already asking writers to have characters say their actions out loud so viewers who are looking at their phones can still follow along.

We are definitively “too high up to touch down” — we are floating in space, divorced from the things that make us feel human, and despite having an infinite amount of content at our fingertips, we end up having this “distant feeling that [we’re] not alive”, as if nothing is worthwhile. The increasing prevalence of AI threatens to profoundly alter even some of our most fundamental human activities, like the creation of art, increasing our sense of alienation as we navigate this new landscape.

And yet, we still have “ancient forces” in our minds, and those need to be respected and worked with, not discarded as if we are above them — doing so leads to this sense of disembodiment and disconnection. We still need someone to point their finger at the moon (a classic Zen phrase) and show us the path. We need to remember that there are sages that have walked in front of us, be they religious figures, like Buddha, Christ, etc., or great philosophical figures like Seneca, Kant, etc., and they have pointed out the way for us, or at least given us a foundation to build upon.

We are not alone in this, and we should be mindful of the virtues, like prudence, that have helped the billions of humans who have lived and died before us make their ways skillfully through the world. If we want to forget those virtues and enjoy our basest animalistic tendencies each time the weekend rolls around, we are free to do that, but we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking that this is all that living is for — most philosophers would agree that there is more to life than partying and consumption. This constant justification of our basest impulses is a uniquely modern phenomenon. I’m not suggesting we feel guilty about them or that we all need to let go of every pleasure, but we should at least be mindful of when we are living superficially and aren’t living up to our ideals, whatever they may be.

This larger perspective — this long view — can serve not just as an interesting view to ponder, but it can provide a sense of peace, framing our seemingly insurmountable problems as just fleeting experiences in an endless cycle, connecting us with something greater than ourselves. Our need to hear wise words from another, to hear stories and lessons, is part of what makes us human, and no matter how disembodied we get, even to the point of replacing our voices with AI, we can always find refuge by relying on perennial wisdom.

The art

This song is about the need for spiritual fulfillment — that hunger of the ancient, pre-modern mind — that lies deep below the surface of our experience. I tried to make art that represents that.

Today, that need is not only largely unfulfilled, but it is obscured and covered up as we indulge in an unending and limitless amount of superficial content, hardly ever even bothering to pay attention to it.

The images in this collage are a mix of AI, public domain, and Creative Commons images. I specifically wanted bad AI images to help convey the absolute absurdity of the times we are living in. If you look closely, you’ll see disfigured human faces, the second-order nonsense of an AI generation I like to call “Pordan Jeterson” (second-order because I do not think highly of the real Jordan Peterson in the first place, to say the least), and images that look fine at first glance, but make less sense the more you look at them. All this is melded together with real imagery, so that it’s unclear what is real and what is simulation.

But you’ll also find important voices of the past shrouded in this cacophony - Laozi pokes his head out of a shrimp cocktail, Toni Morrison looks out from behind an AI (roast beef?) sandwich. And at the center of it all, blending into the background, is that fundamental human need for the divine touch — for something more than the world — in Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam.

I’ll leave you with a question: in this scene, is God’s hand moving closer to Adam’s? Or is it pulling away?